Alzheimer’s disease has had a profound impact on me, both professionally and personally.

After working over a period of 10 years at two different companies on a total of four therapeutic development programs, all aiming to slow the course of AD, I have come to understand the toll that it takes on individuals, families, communities and society as a whole. The numbers are staggering, but so are the personal stories of those impacted.

I suspect you have a story to share. I do too.

After my mother and mother-in-law began to show signs of cognitive decline, I walked a circuitous road to definitive diagnoses. The irony isn’t lost on me: I’ve built a broad professional resume in the Alzheimer’s space, even as I have stumbled into the role of care partner to the matriarchs of our family as the disease steadily progresses and their functioning diminishes.

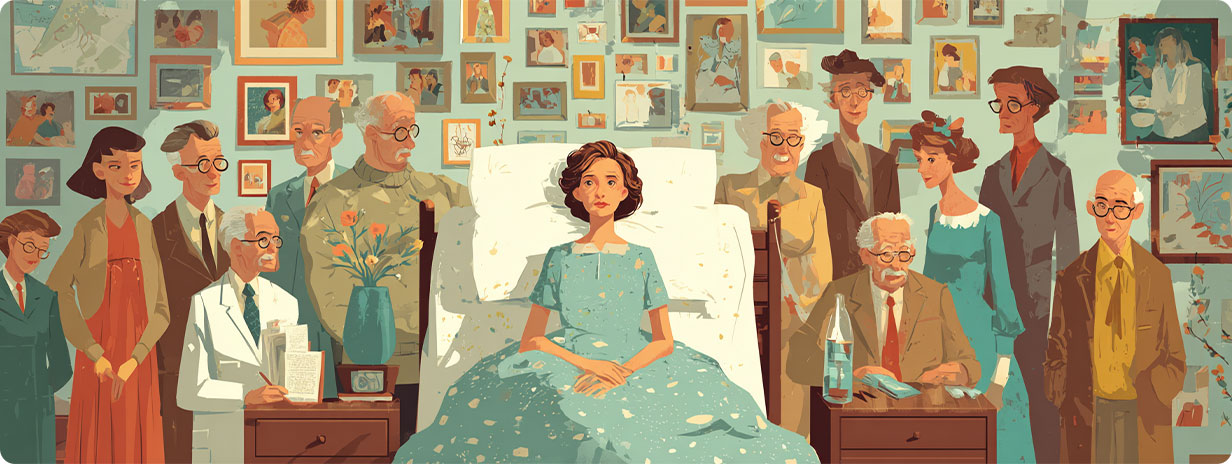

Through it all, I’ve been blessed to travel to communities and academic centers all over the country and meet the heroes living with this disease as well as those advocating for them, whether at the bedside or at the bench. Immersing myself in the stories of the people in the trenches has been both heartbreaking and incredibly hopeful – and, as I’ve encountered them, I feel our stories have converged into a bigger framework.

I’ve learned that we need more conversation, more education and more innovation in this space to truly make an impact. This requires that we bring a broad range of people and experts together – to educate, equip and engage in a new conversation that can further transform lives.

The Family Conversation

After my father’s passing in 2015, my mom began to show signs of occasional forgetfulness, repetition in conversation and increasing disorientation while driving. Eventually, she acknowledged these changes and our family agreed that a cognitive evaluation would be helpful.

However, her otherwise attentive primary care physician seemed surprisingly dismissive about our request. His perspective was – and I quote – “We could give her the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), but she’s going to pass with flying colors. And even if she doesn’t, what are we going to do about it?”

As it turned out, our experience was in many ways reflective of primary care in general. PCPs often lack the time and training needed to detect and assess early signs of cognitive impairment. Lack of familiarity with the latest treatment options for early AD is another barrier.

This changed for us following a car accident and my mother’s subsequent loss of driving privileges. Not only did that represent a loss of independence and a certain degree of freedom, but it also served as a trigger to activate the healthcare system.

NOW her doctor took notice.

All too often, it takes an untoward event to catalyze a diagnosis. Once obvious, it was easy to agree on the need for professional evaluation. But did it really need to come to this?

I confess that my passion for early detection was rooted in a sense of personal failure. I essentially lived next door to my mother during a time when she was progressing through the mild cognitive impairment stage of AD, which is the earliest symptomatic stage. Somehow we missed the best window for early intervention.

How did this happen? How could we, her industry-experienced family members, let alone the healthcare system, have failed her this way?

More broadly, how can the healthcare system support individuals and families who are less connected and less educated, not to mention less supported at home, navigate this insidious disease? And how will society address it sooner in its course, when it can most effectively be addressed?

Thankfully, we were blessed with access to some of the foremost Alzheimer’s experts in the world, who would guide us to a point of clarity. Naming and embracing AD as a family was indeed a liberating step in the journey. But expertise isn’t enough to turn back the clock. By the time we had a definitive diagnosis, mom had progressed into dementia.

I so wish we had initiated family discussions sooner. But I can say that our long journey from these earliest conversations – through primary and secondary care evaluations to individualized care plans – has cemented in me a resolve to see this process accelerated for those who follow behind us.

The Fight

Not only does AD affect the very humanity of the individuals and families living with it – and require of the surrounding community an advanced degree of human empathy and love – but it is also a great leveler. We as human beings long to preserve our own sense of who we are, so we can all relate to the plight of those who are affected by AD. And most everyone has been touched by this disease and, at some level, is concerned that they, too, might succumb to it. Alzheimer’s disease is a fight.

Many in the AD community have referred to the Food and Drug Administration approval of the first wave of disease-modifying agents as “the end of the beginning” of this fight, borrowing from Winston Churchill’s famous speech. The goal in this first phase of addressing this disease should be to deliver on the promise of less worsening. This is a difficult expectation to set, and perhaps even more difficult to manage over time. But for those who are chasing that promise, it is immeasurably valuable. For those not yet convinced of their need for it, it is perhaps less than motivating.

Many individuals are also hindered by denial or avoidance. This is often the case when it comes to conversations between individuals living with AD, their family members and primary care physicians. With so many other seemingly more urgent health matters to address, cognitive impairment can often become deprioritized.

But for those suspecting that they or a loved one are experiencing changes in cognition, there is every reason to exercise full agency and initiate discussions with their doctors regarding these new treatment options, and to do so with hopefulness. In this new treatment era, when more can be done to treat AD, our call to action is clear: We must advocate for seeking care as early as possible.

The Future

As we look ahead, there is reason for optimism. The AD diagnostic landscape has accelerated significantly, arguably outpacing the development of new treatments. This is most clearly exemplified in the plasma biomarker space. This year alone, we saw the first FDA approval of one blood test for assisting in AD diagnosis and another to help PCPs rule out the presence of amyloid beta, a hallmark of AD pathology, and better determine whether additional testing or specialist evaluation is needed. It represents meaningful progress in encouraging earlier intervention.

The science is now moving from disease modification to secondary prevention in the preclinical stage of illness. This is perhaps one of the most exciting developments: It could help boost motivation to treat with both therapeutic and non-therapeutic interventions, including modifiable risk factors, and hopefully finally tip the scales in motivating people to make much-needed lifestyle changes.

As has often been noted, “What is good for the heart is good for the brain.” Bringing this from a realization within the AD community to a broader societal acknowledgement may enable us to have the “family conversation” much earlier. This could lead people with early symptoms to seek care more proactively and ultimately view AD as a truly manageable – and hopefully preventable – chronic disease.

What we need in the AD community is more connectivity, more conversations and even more integrated discussions. Bottom-up solutions at the local and regional levels, with the involvement of many stakeholders who are committed to making an impact, can yield win/win collaborations that recognize social determinants of health and help deliver benefit to everyone in the ecosystem. I believe this is possible, and the time is now.

In a very real way, it is incumbent on each of us who have been touched by AD to help move the goalposts nearer and nearer for those who will follow in our footsteps. As I look to bring more people together, I hope we make an impact in this arena for a long time to come. For the sake of my mother, my mother-in-law and your loved one, we can have it no other way.

Bill Gibson is founder and CEO of Absolute Value Group Consulting LLC. He was previously senior director, Alzheimer’s disease marketing, at Eisai and director, global commercialization, Alzheimer’s disease and diagnostics, at Bristol Myers Squibb.