Dr. Kimberly Smith came of age as a person and physician during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. When she first started seeing patients as a medical student, treatments didn’t yet exist—no AZT, no combination therapies, no PrEP, no anything. She spent countless hours providing patients with comfort and companionship, often in the absence of their family and friends.

Fast-forward nearly four decades, and Smith finds herself among the frontline leaders in the ongoing fight to end AIDS. As SVP and head of research and development at ViiV Healthcare, Smith is in a position to impact millions of people around the world. Yet despite all the turns of the calendar, all the breakthroughs and setbacks and complications, she remains every bit the fiercely determined, deeply empathetic advocate she was fresh out of medical school.

“Once we had medicines, I was never giving up,” Smith says. She pauses, then adds, “And here I am almost 40 years later.”

***

Smith was born and raised in Detroit. She received her undergrad, medical and MPH degrees from the University of Michigan, where she became involved in campus activism. “Anti-racism, anti-homophobia—I thought of myself as a good troublemaker,” she says. “I still do.”

Smith found an immediate home at Chicago’s renowned Rush University Medical Center, where she completed her medical internship, residency and infectious disease fellowship. She stayed following the conclusion of her training, becoming a member of the center’s faculty and, later, principal investigator of the clinical research site for its AIDS clinical trials group.

At Rush, Smith saw parallels between individuals denigrated for the color of their skin and the first wave of AIDS patients, which deepened her resolve to treat them humanely. “The people who were hospitalized—they were my age and, in many cases, had similar politics. I felt connected to them,” she recalls. “Folks were being mistreated in such a dramatic and obvious and angering way. When I saw it, I knew I had to be there. It touched all my buttons.”

The bad days outnumbered the good ones. Smith recalls the emotional toll that treating young patients, many in their 20s, exacted on her and other members of the RUMC care team. In some cases, patients were surrounded by family; in others, they were alone. Smith speaks with obvious pride about how the hospital staff “became their support networks,” even as it became clear that many of them would never leave the hospital.

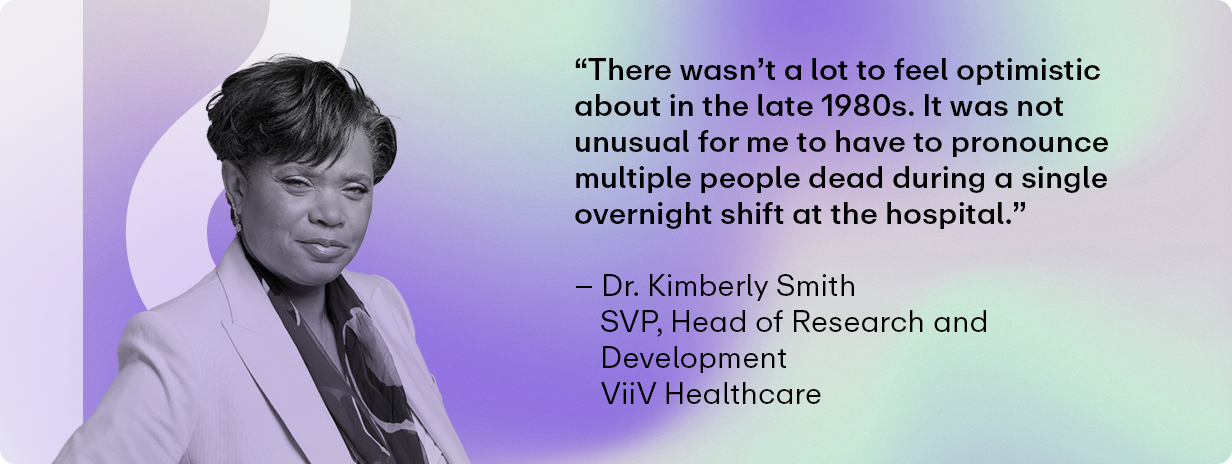

“There wasn’t a lot to feel optimistic about in the late 1980s,” Smith says plainly. “It was not unusual for me to have to pronounce multiple people dead during a single overnight shift at the hospital. That was the way it was.”

Even amid the grim prognoses, Smith was fascinated by HIV from a scientific standpoint. Epidemiologically, the virus was unlike anything scientists and physicians had previously encountered. “It knocked out immune systems in a way nobody had seen before,” she explains.

Combination therapies arrived in the early 1990s and, by mid-decade, scientists knew they could control the virus to some extent. At the same time, the tolerability of those regimens presented challenges of their own for treating physicians.

“There were all sorts of reasons for people not to want to take the medicines, because sometimes it felt like the medicines were worse than the disease,” Smith says. “We were prescribing medications to help people tolerate their medications.”

She stresses, however, that this represented a better problem than the ones she and her physician peers encountered during the epidemic’s first wave. And then there were the moments of joy and disbelief: “You’d have these Lazarus situations, where people got up from their deathbed and eventually recovered. Simply amazing.”

Twenty years into her career, Smith received a call from John Pottage, a former director of Rush’s outpatient HIV clinic. She considered him a mentor, which made his offer of a role leading clinical development at ViiV all the more alluring.

“I never saw myself going into pharma. I was an academic researcher who took care of patients, right? That was my career,” Smith says.

Pottage’s presence, and the credibility it conferred in her mind, proved the deciding factor. “In the last conversation I had with John about whether I’d come over, I said to him, “John, if there’s ever a point where somebody asks me to do something that compromises my integrity, I’m going to quit,’” she continues. “He looked back at me and said, ‘Yeah, me too.’”

The role proved an immediate fit. “You could tell immediately that Kim knew exactly who she was and what she stood for,” says ViiV VP and head of clinical development Sherene Min. Min found herself equally charmed by the dichotomy between Smith’s commanding professional presence and her “wonderfully quiet side.” including plenty of time spent gardening.

“It’s a beautiful contrast to the high-stakes world we operate in. It shows her dedication to cultivating life and beauty in her own space,” Min says.

Asked to share something her colleagues may not know about her, Smith acknowledges and celebrates the contrasts. “While I may seem tough, I am really a pushover who is quick to tears.” She’s also an avid fantasy football player.

***

Nearly 12 years later, Smith characterizes her move to ViiV as “one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. Helping patients on a one-to-one basis will always be something I cherish, but here I have the opportunity to impact so many more people around the world.”

She lauds ViiV’s commitment to making its HIV treatments more accessible by facilitating the manufacture of generic versions of dolutegravir and other drugs, as well as the company’s overall operating philosophy. “We don’t make me-too drugs and we don’t copy anything that’s already out there. Every decision is dictated by what patients want.”

Increasingly, the answer to that last question is longer-acting medicines. ViiV now counts Apretude, a HIV PrEP treatment injected every other month, and Cabenuva, a complete HIV regimen administered monthly or every other month, among its treatment offerings.

“If you’re not living with HIV, you can’t fully appreciate the trauma that comes with the daily reminder of having to take a medicine,” Smith says. “For many people, the day they were told they were HIV-positive was the worst day of their life. Now imagine having to relive that every day when you receive your medicine… Longer-acting medicines are life-changing. They’re liberating and transformative.”

Smith hopes that these medications—and the within-our-grasp possibilities of a full-on cure and containing HIV without medicine—will be part of her legacy. Mostly she wants to be remembered for remaining true to the cause through thick and thin: “I cared about people and was willing to stick my neck out to fight for what I think is right.”

To that point, Smith believes the battle against AIDS demands the same heightened degree of attention as it did when the virus first emerged in the 1980s. The statistics remain sobering: In the United States alone, an estimated 1.2 to 1.3 million people are living with HIV, while another 35,000 to 38,000 new infections are reported every year. Those numbers suggest to Smith an urgent need to get people living with HIV on treatment and to ensure that vulnerable individuals, especially those in communities with high prevalence, have access to preventive care.

“If we do this right, we can start getting toward the end of the epidemic,” she says.

Asked whether we actually are doing it right, however, Smith pauses before responding. “We might be doing it right, but we’re not doing it enough.” The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) set a 90/90/90 goal for 2020—90% of people with HIV knowing their status, 90% on antiretroviral therapy, 90% with undetectable viral load—but came up short. The organization similarly expects to miss the mark on its 95/95/95 goal for 2025.

In Smith’s mind, this isn’t in the neighborhood of acceptable. “To hit the 2030 targets, we have to do something different,” she says forcefully. “Are we talking about HIV enough? Maybe we’re not.”

Given the sharp cutbacks to U.S. government funding for HIV research, one might think that Smith’s positive outlook will soon be put to the test once anew. But while she acknowledges a rise in AIDS deaths and new cases over the last six months, she senses genuine determination in the broader medical and scientific communities to reverse these trends and push closer toward a cure.

“The advocacy mindset that was present at the start of the AIDS epidemic is still strong,” Smith says. “Folks are ready to fight. I remain very positive that we can get to where we need to be.”

Have you worked with a life sciences leader whose personal and professional story would make for an interesting Kinara profile? Drop us a note at hello@kinara.co, join the conversation on X (@KinaraBio) and subscribe on the website to receive Kinara content.